Trump adviser proposes broader cybersecurity oversight for private-sector critical infrastructure

A top White House official says the U.S. government may have a more extensive role to play in defending computer networks associated with American critical infrastructure, even though most are owned and operated by the private sector.

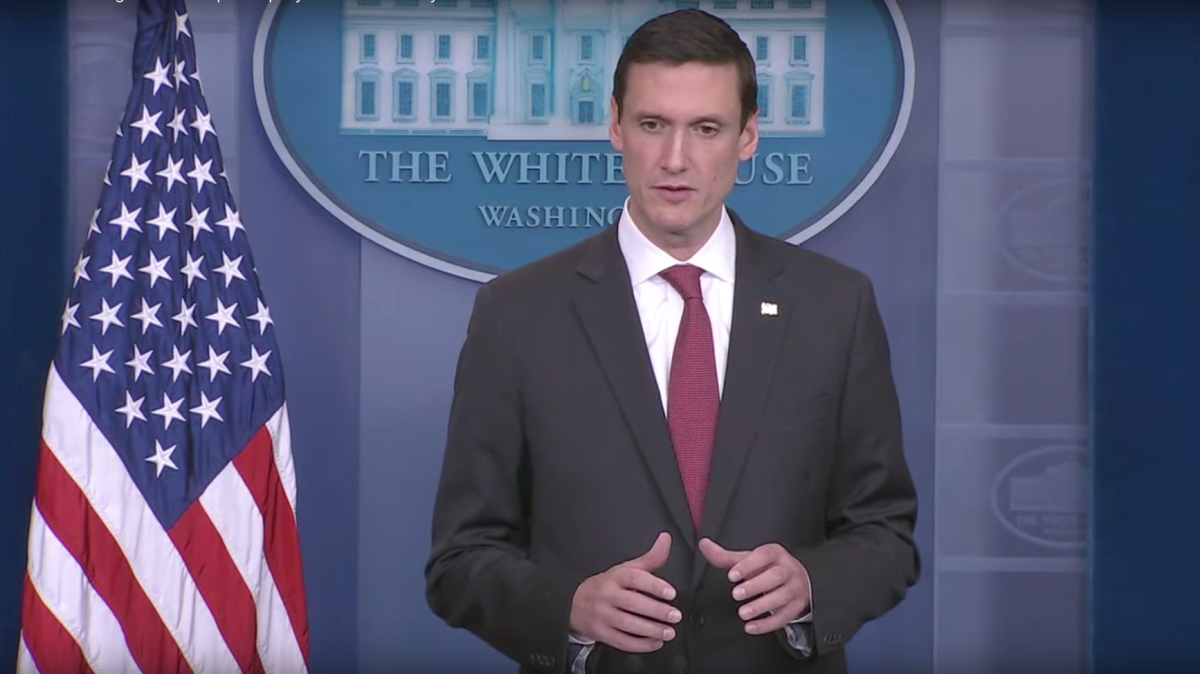

Thomas Bossert, assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism, told an audience of former intelligence and defense officials Wednesday in Washington, D.C., that there are certain narrowly defined cases where the Defense Department could be more closely connected to companies and organizations that handle what the Department of Homeland Security labels as critical infrastructure. The designation applies to 16 different U.S. business sectors, including manufacturing, emergency services, energy and financial markets.

There are a number of different federal agencies that are currently involved in defending the private sector from computer intrusions: the NSA, FBI, DHS and the military’s U.S. Cyber Command. Some former intelligence officials, like ex-NSA Director Keith Alexander, believe, however, that this multi-agency approach is too “stovepiped” and can confuse potential victims about whom to notify about cybersecurity issues.

Bossert, who broadly described the Trump administration’s cybersecurity plans during Wednesday’s appearance at the 2017 Intelligence and National Security Summit, was answering an audience question regarding how Cyber Command might work in the future with U.S. critical infrastructure companies that are under attack.

The White House adviser’s vague proposal about greater integration between the U.S. government and private sector referenced Israel’s cyberdefense model, which allows some government agencies to monitor and block cyberattacks in realtime that occur against business networks.

Over the last several years, many American companies have balked at the suggestion that the government should have greater access and visibility into their networks. Unauthorized disclosures by U.S. intelligence contractors — namely Edward Snowden and Harold Martin — contributed to this lack of enthusiasm. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies often get the call only after a breach occurs, rather than during a disruption, when it’s possible to gather more information about attackers.

In the meantime, there are regular reports about foreign intelligence agencies or their proxies actively hacking U.S. enterprises. In March, the Justice Department indicted two Russian spies for their part in orchestrating a hacking operation into U.S. technology giant Yahoo. National security experts say it’s not uncommon for nation state-backed hackers to steal intellectual property and non-defense-related secrets from commercial organizations.

In brief terms, Bossert stated that the Trump administration would not tolerate and planned to retaliate outside the bounds of cyberspace against any country that continued to sponsor cyber-operations against American companies. If the Chinese were to begin engaging in widespread economic cyber-espionage again, he explained, then the White House would call Beijing out publicly. China agreed during the Obama administration to stop cyber-enabled spying on U.S. businesses.

Speaking about how the U.S. should retaliate to such an action, Bossert was more direct, stating that offensive cyber-operations — retaliatory hacks — are far from the only option to punish bad actors. They often achieve very little, he said, aside from escalating tension and encouraging additional data breaches. Sanctions and diplomatic action have a more important impact, Bossert said.

“There’s very little reason to believe that an offensive cyberattack is going to have deterrence on a cyber-adversary,” Bossert said.