How the US military used a creepy island to test cyberattacks on the grid — in the middle of a pandemic

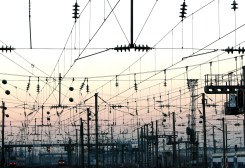

The U.S. government officials trying to test the country’s ability to respond to a major cyberattack thought they had pulled out all the stops. Engineers had planned to simulate the kind of security incident that would cause an electrical blackout, after all, and had even planned to hold the event on an isolated island off the coast of New York.

Even with all that preparation, a once-in-a-century pandemic still wasn’t in the script.

Until this year, National Guard personnel, Pentagon contractors and engineers at big U.S. utilities would typically gather in person to run through exercises involving dire scenarios, from a weeks-long power outage to a mock attack on utility computers that appeared to delete data.

In October, though, COVID-19 forced planners from the departments of Defense and Energy to figure out how to run the event virtually, with participants plugged in from around the country. And they used the pandemic as another opportunity to prepare for the unpredictable.

The goal of the recurring effort, which is backed by a $118-million Pentagon program, is to try anticipate how state-sponsored hacking groups could sabotage key utilities. The exercise provides important defensive insights for some of America’s largest electricity providers, and comes as an increasing number of hacking groups have taken an interest in the industrial control systems that those utilities use to deliver power.

This year’s unusual setup ended up being “useful for modeling how people would respond remotely to a widespread cyberattack,” said Walter Weiss, a cerebral program manager at the Pentagon’s R&D arm — the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency — who helped plan the exercise. “That just added additional realism.”

Organizers allowed utility engineers and researchers to participate, despite the coronavirus, by accessing software tools used to defend against the simulated attacks. While most participants joined remotely, a diehard crew made the trek to the austere, windswept spit of land called Plum Island, off Long Island, that has hosted past exercises.

The exercise in October tasked mock electric utilities, staffed by real utility workers, with restoring power after a debilitating set of simulated cyberattacks. Participants had to use a generator to gradually restart a power system, substation by substation, and test DARPA-funded forensic tools in the process.

Weiss pointed to a 2019 threat assessment from U.S. intelligence agencies that said that China and Russia had the ability to use cyberattacks to, respectively, temporarily disrupt natural gas pipelines and electric distribution networks.

The exercise planners drew on real-world incidents, too. The 2015 suspected Russian cyberattack on Ukrainian electric infrastructure, which cut power for some 225,000 people, blinded utility operators to what was going on in power distribution networks. Plum Island combatants were trying to avoid a similar type of loss of visibility.

“That’s a great wake-up call and resonates with utilities we’re trying to work with,” Weiss said.

An eerie setting

The latest exercise was the seventh, and final drill, on Plum Island under a DARPA program called Rapid Attack Detection, Isolation and Characterization Systems (RADICS).

The number of electric utility employees and government contractors allowed on the island this year was kept under 30. Participants were regularly tested for the coronavirus before and after they stepped off the ferry and onto the island, which has a spooky effect on visitors that’s hard to overstate. (Plum Island has also been the government’s home for studying animal-borne diseases.)

“We had our own dedicated ferry schedule and didn’t interact with anyone other than the RADICS team, so it felt a bit more isolated,” said Tim Yardley, a senior researcher at the University of Illinois, who spent six weeks on Plum Island setting up infrastructure for the exercise. “The eerie part for me was the drive across the country [during a pandemic].”

Engineers installed high-speed fiber optic links on the island to allow people to take part digitally. They also helped configure a virtual private network so that members could log into the exercise from their laptops.

Yardley said participants were initially concerned that the remote environment would sap the exercise of its hands-on value. But the takeaway instead, he said, was that “you could actually do an incident response and make this work.”

“The tools were successful in that way,” said Yardley, a veteran of multiple Plum Island drills. “They automated many of the things that would take a person a lot longer to do in person.”

“Was it ideal? No,” he continued. “But technology could serve to aide in this way. I think it was eye-opening for many of the participants.”

Weiss and Yardley said the exercise participants were able to use the DARPA tools to help stabilize the grid on Plum Island, and eventually restore power.

Spotting the lie

The RADICS program funds technology including data-ingesting software that sorts normal from suspicious activity on a power network, and a system for conducting emergency communications between a substation and a control center.

Particularly handy during the latest Plum Island exercise was a dashboard that allowed users to accurately monitor network activity “even if your own systems are lying to you,” as Weiss put it. That means if a control panel is telling a utility operator that a substation is running normally, when it really isn’t, the dashboard would have been able to spot the lie.

The 2015 attack on Ukrainian power companies remains a stark example of what might go wrong when detection fails. No cyberattack anywhere near that magnitude has happened on U.S. electric infrastructure, but utility operators still prepare to defend against such threats.

“Two things a cyberattack can do to the grid are make it not tell you the truth, or make it not work how you expect it to work,” Weiss said. “So in general, the whole scenario is about finding what parts of the grid are doing that to you.”

With the Plum Island project coming to a close, DARPA has handed off the software tools to the Department of Energy, which works closely with utilities, to introduce more of that technology out into the field, Weiss said. Some of that is already happening. New Jersey-based company Perspecta Labs, for example, is looking to market its malware-hunting system to utilities.

Valuable data in the vault

Six weeks after the Plum Island experiment in October, the U.S. government held another elaborate cybersecurity drill for the power sector.

The “tabletop exercise” hosted by the Department of Energy on Dec. 9 included executives from some of the biggest power companies in the U.S. Officials from multiple national security agencies were also on hand, according to exercise planners.

Like Plum Island, the exercise envisioned aggressive cyberattacks on the electric sector by a foreign adversary. Participants had to talk through how they would respond to the incident, trade intelligence and revert to backup power solutions. It’s part of a long-running DOE exercise series known as Liberty Eclipse, which has historically included the Plum Island program.

“Shaping these conversations under blue-sky conditions can help mitigate redundancy, bureaucracy, and frustration down the road,” said Brian Harrell, a former senior Department of Homeland Security official who is now chief security officer at renewable power company Avangrid, and who participated in the Liberty Eclipse tabletop exercise.

The Department of Energy did not respond to interview requests for this article, though the department said in a statement that the goal of Liberty Eclipse was “to validate tools that enhance information sharing capabilities and identify threats to the energy sector.”

Grid-focused cybersecurity officials in the government will be studying lessons learned from both sets of exercises for some time. It’s an example of the institutional knowledge on the resiliency of the grid that the Biden administration will inherit, and need to use, as foreign adversaries continue to probe such infrastructure.

For his part, Yardley is now preparing to send several hard drives of exercise data to U.S. government officials, including network traffic from the simulated attacks. He said he hopes the government will eventually make the data public so that researchers and the broader power industry can study it.

That kind of data is valuable, Yardley said, because “obviously, you can’t go download off the internet data of a utility being attacked by what looks like a nation-state.”