There’s a new open-source project to detect cellphone-snooping technology

In October 2016, during popular protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, a technologist named Cooper Quintin took a red-eye flight from San Francisco to North Dakota and made his way to the Standing Rock Reservation.

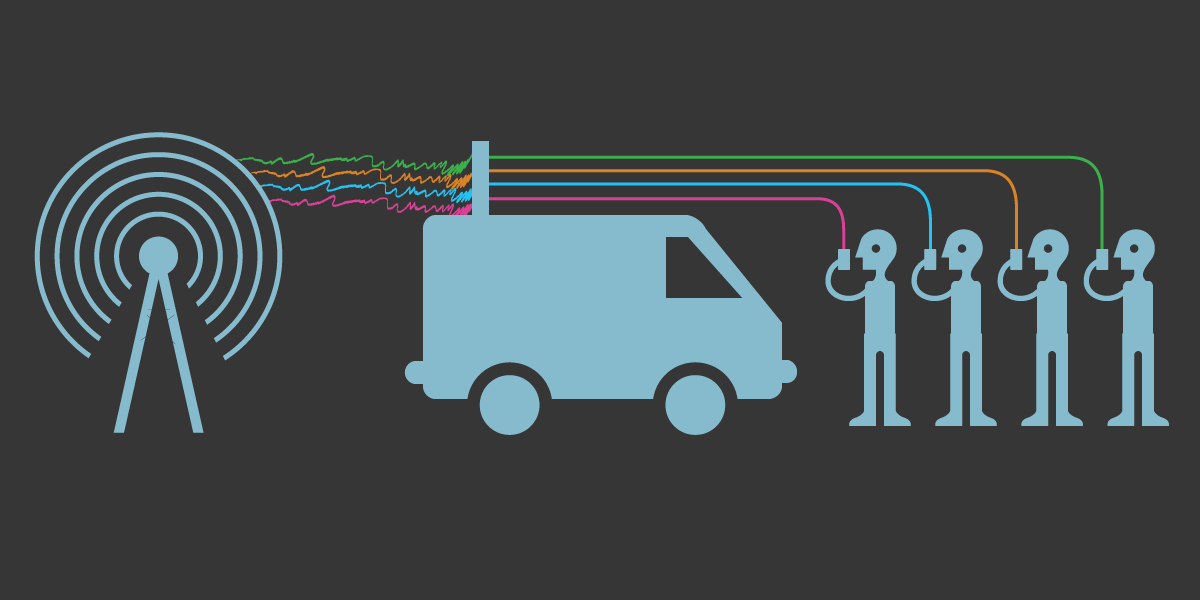

There had been reports of police surveillance of the protesters, and Quintin suspected that involved a device known as an IMSI catcher or cell-site simulator. The technology, sometimes referred to as a Stingray, spoofs a cellular tower, tricking your phone into revealing its location. From there, data-stealing attacks on the phone are possible. Police and spies use the gear for surveillance.

At Standing Rock, Quintin took out his software-defined radio, scanning for abnormal signals, and opened up an Android app known for spotting IMSI catchers. He didn’t get any hits.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” said Quintin, a security researcher at the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. He was using technology designed for 2G wireless networks, leaving him blind to IMSI catchers on 4G networks, if they were indeed there.

Nearly four years later, he has a better idea of what he’s doing. This week, Quintin and an EFF colleague who goes by Yomna are releasing an open-source project they designed to track IMSI catchers running on 4G networks. The Crocodile Hunter, as the software and hardware kit is called, includes code that measures an area’s cellular network, and an application programming interface that gathers data and shares it with other researchers.

“None of the previous IMSI catcher detector apps really do the job anymore,” Quintin said in a video recording to be shown Thursday at the DEF CON virtual hacking conference.

The goal is to hone the Crocodile Hunter’s accuracy over time to more clearly map where mobile-surveillance devices are deployed. “I’m specifically interested in how often they are being used to spy on protests and uprisings in the U.S. and around the world,” Quintin told CyberScoop. The gear will be tested in Washington, D.C., and New York City, and in Latin America through the Fake Antenna Detection Project, he said.

If the tech works, it should get plenty of hits. Cell-site simulators have long been popular with both local cops and federal law enforcement agencies. The Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency used the devices more than 400 times from 2017 to 2019, according to government records obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union.

There’s also the chance that the Crocodile Hunter will stumble upon an espionage operation. In March 2018, DHS’s cybersecurity agency acknowledged that there appeared to be unauthorized IMSI catchers in the Washington, D.C., area. A subsequent report from Politico said Israeli spies were likely involved.

In hunting for IMSI catchers, technology only gets you so far. Once you have accurate coordinates of a suspicious cellular base station, you typically have to uncover the device in person. If the Crocodile Hunter gains traction, that could lead to some awkward encounters between tech-savvy sleuths and whoever is on the other end of the signal. “I have no idea how I would react in that situation,” Quintin said of the possibility of a run-in with a spy.