Researchers unearth hacking group that’s been active, yet undetected for years

During a recent investigation of a series of cyber intrusions into an unnamed high-value target, threat intelligence researchers with SentinelOne’s SentinelLabs team discovered nearly 10 hacking groups associated with China and Iran.

This isn’t necessarily new when dealing with significant targets, sometimes referred to as a “magnet of threats” in cybersecurity, as they attract and host multiple hacking efforts simultaneously. But among the cohabitating groups, researchers unearthed a previously unknown group that seems to be operating in alignment with nation-state interests and perhaps as part of a high-end contractor arrangement.

The group — dubbed “Metador” in reference to a string “I am meta” in one of their malware samples, and because of Spanish responses from the command and control servers — shows signs of operating for at least two years, with signs of extensive resources having been poured into development and maintenance in pursuit of what are likely espionage aims.

The group attacks with variants of two Windows malware platforms deployed directly into memory, with indications of an additional Linux implant, and are capable of rapid adaptations. According to the researchers, the group noticed that one of their victims had begun to deploy a security solution after initial infection and “quickly adapted” in response. “That swift response only did more to pique our interest,” the researchers said.

The group has primarily targeted telecoms, internet service providers and universities in the Middle East and Africa, the SentinelLabs researchers Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade, Amitai Ben Shushan Ehrlich, and Aleksandar Milenkoski said in findings published Thursday. But it’s likely only a fraction of the group’s true scope is known, as it manages its infrastructure in such a way to limit the ability to connect one victim to another, using a single IP address per victim, for instance.

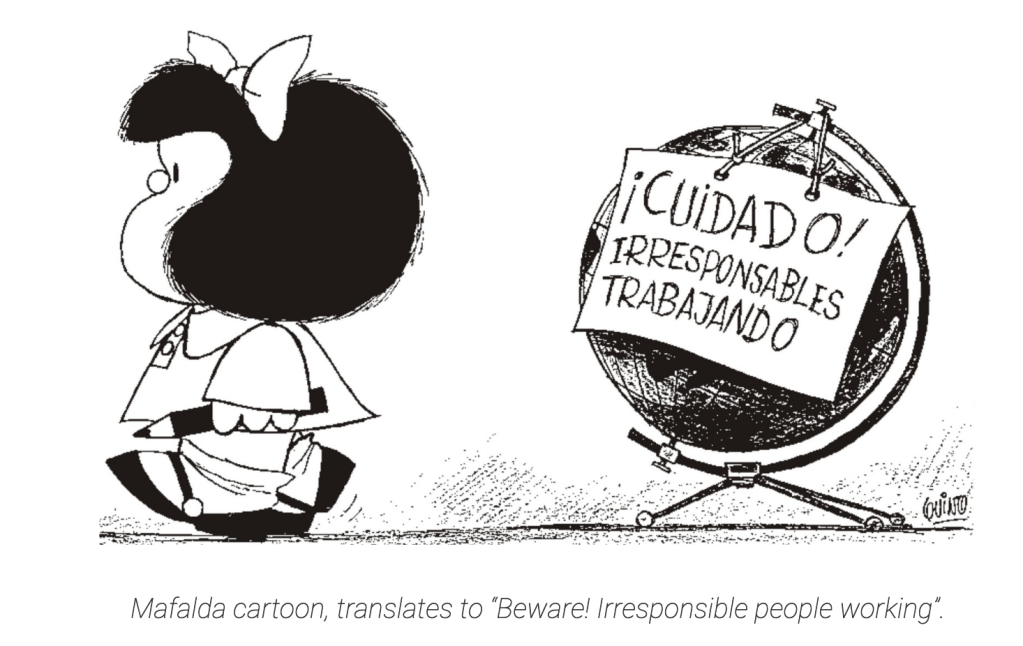

Reliable attribution wasn’t possible, the researchers said. The developers are clearly fluent in English, with signs of more casual English — “LOLs” and smiley faces, the researchers said — alongside “highfalutin” English. Spanish is also used throughout the code of “Mafalda,” one of the two malware platform variants developed by the group. Mafalda is the name of an Argentine cartoon character, popular with the Hispanic diaspora dating back to the 1960s as a means of political commentary, the researchers said.

“It kind of points to the fact that Argentina is this not-so-hidden gem of offensive talent that people forget,” Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade, principal threat researcher at SentinelOne told CyberScoop. “There’s so many companies that have recruited unbelievable talent from Argentina for past 10, 15 years … and it’s a nice reminder that there is all this talent that you can easily tap into. And the question is, who is tapping into it?”

Another interesting pop culture reference was buried in Mafalda’s code: A lyric from the 90s song “Ribbons,” by British pop punk band The Sisters of Mercy: “her eyes were cobalt red, her voice was cobalt blue.”

“Whilst these cultural references are interesting fingerprints, they do not lend themselves to a clear sense of attribution nor a cohesive attributory narrative beyond the possibility of a diverse set of developers perhaps indicative of a contractor arrangement,” the researchers wrote.

The signs of active development and its success at detection for so long has the researchers worried, with hopes that the wider threat intelligence community and others will take the technical indicators shared in the report and look for their own signs of Metador.

“Their operations are massively successful precisely in that they’ve eluded victims, defenders, and threat intel researchers until now despite maintaining these malware platforms for some time,” the researchers wrote. “We consider the discovery of Metador akin to a shark fin breaching the surface of the water. It’s a cause for foreboding that substantiates the need for the security industry to proactively engineer towards detecting the true upper crust of threat actors that currently traverse networks with impunity.”

Guerrero-Saade said that the group seems to him as having “capabilities that I think are representative of folks with a deep well of experience who’ve done this before, and they’ve done it at a professional level, but are in a shop or in an arrangement that still makes choices that the true upper crust wouldn’t make.”

But the group offers a harbinger of the breadth and level of activity is going unnoticed, Guerrero-Saade said.

“What worries me is, in a world where hacker for hire is becoming more popular, where the enablers are becoming less identifiable as corporations … how are the talents of the 1 percent that eventually leave government for a better life, how is that trickling down? And what pockets are they ending up in? And how capable are we of tracking them?”