DEF CON Voting Village takes on election conspiracies, disinformation

The DEF CON Voting Village made headlines for giving hackers access to voting machines and putting election vulnerabilities on full display when it first launched in 2017.

But in the era of the “Big Lie,” the unfounded theory of election rigging in 2020, the village has another — and possibly more challenging — mission.

“Today, the main thing is still the same — tell what are the real vulnerabilities — but fight against conspiracy theories, misinformation, claims of hacks that didn’t happen, claims of weirdness that didn’t happen,” said Harri Hursti, the co-founder of the Voting Village and a pioneer election security researcher.

This year at DEF CON, which wrapped up Sunday in Las Vegas, the Voting Village took place against a backdrop of perhaps the most contentious time for election administrators in decades. Aside from working through COVID-19 modifications, public questioning of election administration has reached fever pitch.

Election offices are, at times, buried in records requests looking to expose fraud. Elections officials in Colorado and Michigan stand accused of giving unauthorized access to voting infrastructure in a quixotic effort to prove the 2020 election was stolen from former President Donald Trump. Election officials from Georgia in June detailed the threats they’d received from Trump supporters, a disturbingly common report across the country over the last two years.

That context informed some of this year’s programming in the village. Staffers from Maricopa County, Arizona, home to some of the most intense post 2022 election conspiracy theories, gave a presentation on how their elections work. And Nicole Tisdale, a former National Security Council staffer, talked about how disinformation and misinformation targets minority communities to suppress votes.

The unprecedented pressures on election administrators in the wake of the 2020 election has put people like Hursti, a longtime critic of the election equipment industry, in the position of repeatedly explaining that while legitimate vulnerabilities can be found, there’s no evidence of widespread manipulation or fraud. Even as people from the election industry are harsh critics of the Voting Village, they all generally agree on the main point: There is no evidence of widespread manipulation of voting systems to rig the 2020 election.

Nevertheless, he said, there remains a gap between election security researchers and the hacker community more broadly and the election vendors.

“In almost every other industry than elections, the gap is closing and is has been steadily closing,” he said. “Other industries, especially in the critical infrastructure area, have understood the value of the hacker community, the security community, to work together,” he said. “The election space seems to be stuck to 30 years behind.”

Election officials and the vendors argue that things have improved, and have been critical of the Voting Village almost from the start. Ahead of the 2018 Voting Village, for instance, the National Association of Secretaries of State called the village a “pseudo environment which in no way replicates state election systems, networks, or physical security,” BuzzFeed reported at the time.

Vendors point to their own multi-layered security procedures and the development of vulnerability disclosure programs in recent years, such as the program announced by Election Systems & Software in 2020 at DEF CON’s sister convention, Black Hat.

The problem isn’t with the research community at large, said Ed Smith, director of Global Services and Certification at voting equipment manufacturer Smartmatic, the company that’s suing Fox News and right-wing network One America News for defamation for claims its machines were used to manipulate the election (Smith would not discuss the cases).

The issue is this particular voting village, he said, which he described as “unorganized” and said had some “structural problems,” such as unreasonably tight timelines for vendors to agree to cooperate — which Hursti disputes — and a possibility that vulnerability claims create sensationalized headlines that become hard to rebut.

“The industry has been stung,” he said, pointing to a wave of headlines in 2018 about 11-year-old children hacking replica voting systems. It’s hard for corporate executives to agree to fully participate after an experience like that.

“Let’s say there’s somebody simply not competent, they get access, they write up all these fanciful claims,” he said. “We put out a rebuttal saying, ‘No, none of this is correct.’ What’s going to get the airplay?”

Smith added that voting equipment manufactures contract with third-party examiners, on top of their own internal security procedures. He also said he agrees that “crowdsourcing the finding of vulnerabilities is huge,” under the right circumstances.

Ben Hovland, a Democrat appointed by Trump to serve on the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, told CyberScoop there’s been “an enormous amount of progress in a relatively short time,” since the Russian interference operations during the 2016 election. Over the years, there’s been progress in the relationship between states and the federal government, the vendors and the local officials, and even between the security researchers and the community.

“So often in these conversations one of the, you know, the baseline is if people are operating in good faith, if they want to support our democracy, I think that is always an important common ground,” he said. “And then it’s figuring out how to work together to find solutions.”

Hovland pointed to the talks from Maricopa County and Tisdale as examples of where the Voting Village gets it right. But he also sees how some might be reluctant to take part.

“If the Big Lie highlighted anything, it is the importance of being honest about our elections, being precise, being conscious of the fact that things can be taken out of context,” he said. “Historically, I think, there’s been some sensationalism.”

But for the average security researcher who comes to DEF CON once a year to see the latest developments and get hands-on training, the Voting Village was a good time.

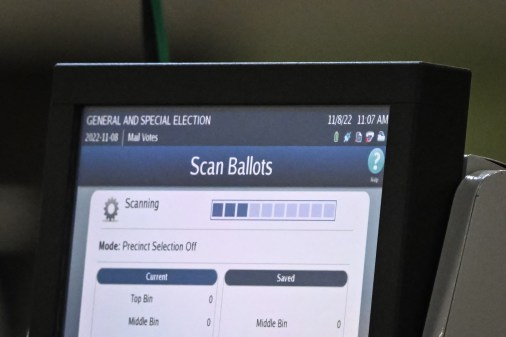

“My interest is to make sure we have election integrity,” said a man who asked to be called “Bobby the Fish,” who was examining a ballot processing machine. A frequent DEF CON attendee, Bobby said that examining the machines helps him continue to explain to people, even in his own family, just how wrong the claims of widespread manipulation are.

“I’m horsing around with these machines because I’m trying to understand what the board looks like, how different things are programmed, what the integrity of these are, just to try and understand it from the technology level,” he said.

At next year’s DEF CON, Hursti said attendees can expect even more devices to hack with the addition of voter registration systems and a wider range from the range of technologies that make up modern elections.