Federal agencies often don’t know who’s attacking them online, OMB says

In nearly a third of the cybersecurity incidents reported to the Department of Homeland Security by federal agencies, there was no information about what kind of attack took place or where it was targeted, officials said Wednesday.

In the annual reporting required by the 2014 Federal Information Security Modernization Act or FISMA, “most agencies didn’t have a handle on where the threat was coming from,” White House Office of Management and Budget official Joshua Moses told a federal advisory panel.

“Nearly a third of the the incidents that were reported to Homeland Security last year did not have an associated threat vector or attack vector specified in the reporting,” he explained to the Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board during an update on OMB’s cybersecurity activities.

Experts say that while it may not matter for the purposes of foiling any one particular attack, knowing the details of an organization’s threat environment — who might be trying to attack it — is nonetheless an important part of understanding and managing that organization’s cyber risk overall.

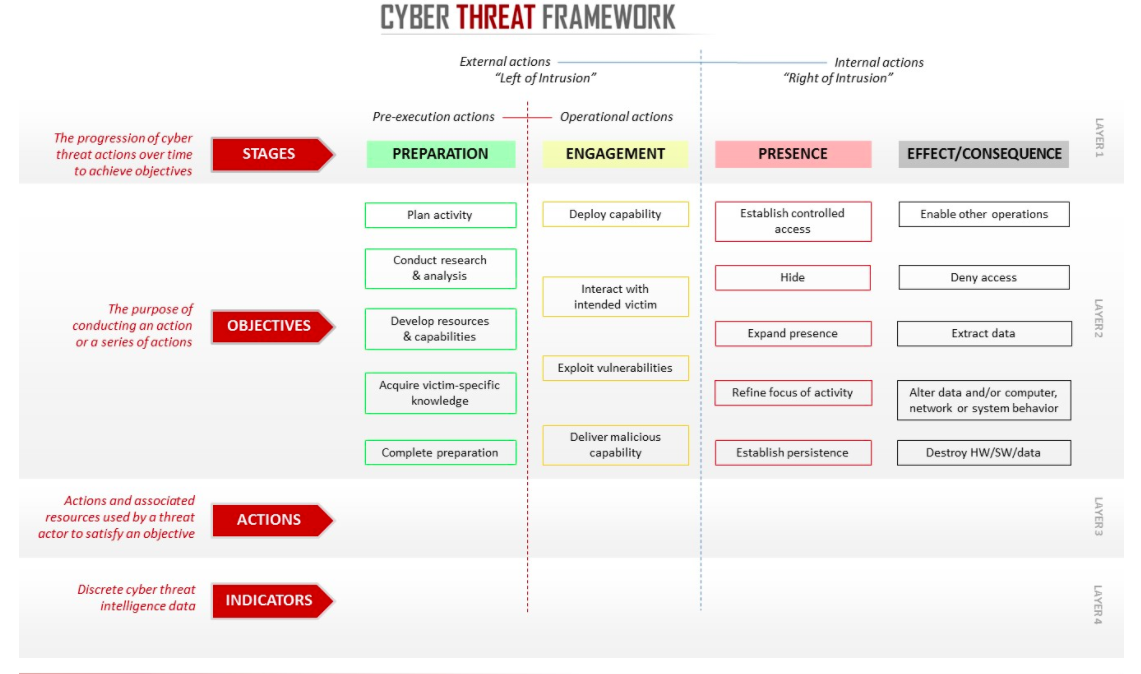

Moses said that to advance that understanding, and try to improve threat and attack vector reporting, U.S. intelligence officials had prepared a matrix looking at the attack lifecycle and delineating various threat activities. The goal is to provide a set of common definitions and understandings that the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, or ODNI, calls on its website a “Cyber Esperanto.”

“We’re trying to get some better sense of what [attack] probabilities are today through measures such as the [cyber] threat framework that the director of the national intelligence has circulated,” Moses said.

Cyber Threat Framework prepared by the office of the director of the national intelligence, or ODNI.

Moses said that security agencies like DHS and the NSA were taking the lead on identifying possible threats to federal networks, adding that OMB’s role over the next couple of months was to “really to bring that [information] all across the dot-gov, to make sure everybody has access to that information to understand their threat environment.”

The ODNI website says that while the threat framework is not a mandatory reporting tool yet, “since the framework is the preferred approach for providing a consolidated threat picture to senior U.S. government leaders and policy makers, we expect reporting agencies will increasingly include cross-references and linkage to the framework in their [cybersecurity] activity reporting.”

The expectation is that over time, “the transparency and simplicity of the framework, the commonality it provides, and its ability to enhance information sharing and facilitate understanding will promote further adoption and use,” the website adds.